International development in Uganda

A story of personal empowerment in Uganda and at home

My flight landed in Entebbe, and Uganda greeted me with the soft blush of morning light. The air was warm, and a short transfer away, Lake Victoria shimmered like a sheet of polished silver. We sat for breakfast on a terrace overlooking the valley and lake - a serene, unforgettable welcome to Africa.

In contrast, we continued our journey through the vibrant pulse of Kampala. The streets buzzed with life: mopeds zipped past, piled impossibly high with sacks, crates, a mirror, people, and even the occasional goat, clinging on like a seasoned commuter. Street vendors called out from roadside stalls beneath concrete buildings. Women passed by, dressed in colourful clothes, some balancing goods on their heads.

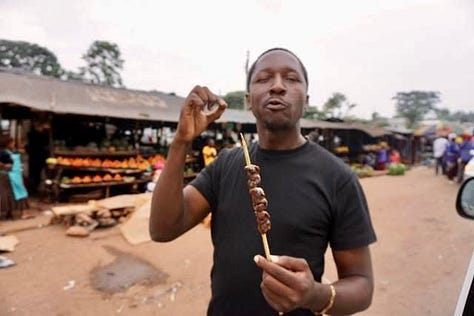

In Jinja, we paused briefly by the roadside for a comfort break. A row of shanty stalls greeted us, with delights for the passing trade. Women sat on the dusty floor selling piles of oranges. Stalls sold hot spicy maize, and Rolex - a flatbread rolled with vegetables. My curiosity led me to try a skewer of gizzard, a local delicacy with an acquired taste.

As dusk approached, we reached Mbale and settled in for the night. Travel after dark isn’t advised here - the roads are unpredictable. We booked a table at a local restaurant that didn’t have a menu. We made a few suggestions for food and reached a mutual agreement on chicken and chips. A delivery of live chickens tied to the roof rack of a car arrived about 30 minutes later, and around 1.5 hours after that, our chickens were served up. We tucked in, appreciating the effort that went into the dish. I quickly realised there was a difference from my usual M&S roast chicken. This one was the ultimate free-range variety - it had clearly had a job as barnyard bouncer with drumsticks of steel before it met its fate.

At first light, we pressed on toward Kapelebyong District, near Kumi. The landscape began to shift. The minibus jolted and swayed over red-dusty, uneven tracks, winding through open woodland. The trees thinned, the air grew drier, and the road became a ribbon of ochre leading us deeper into the heart of Uganda.

The anticipation of our arrival was palpable. The locals knew our visit signalled the presence of donors who had stood behind their community, and their welcome was never anything short of jubilant. We turned the final bend and arrived at the school we visited. A walking sunrise emerged through the swipe of the large bus wipers - an explosion of colour and warmth leading us into the community.

Around a hundred people had gathered, their clothing a radiant mosaic of culture and celebration. Children in bright green school uniforms skipped beside mothers wrapped in vibrant skirts and patterned headscarves with babies tied to their backs.

Teachers stood proud in crisp shirts and ties. The air pulsed with song and dance, and above all, one woman’s ululation soared - a piercing, joyful cry that welcomed us to their culture. The crowd danced in front of the bus, leading us through the way. Having previously worked as a teacher, the opportunity to support fellow teachers and work with students in a rural African community was both exciting and rewarding.

The first few days humbled me. I felt the happiness within the community, which I had felt was lacking back home. The children met us with broad, unforgettable smiles, their eyes bright with curiosity and warmth. We visited many schools, each of them giving us the warmest welcome through song and dance - some we were invited to join in (excuse the mum dancing!)

What amazed me most was their resourcefulness. Nothing was wasted. A discarded water bottle became a toy, a tool, or a treasure. Their creativity was boundless, born not from abundance but from a spirit of making the most of what they had. We played sports, and though barefoot, they put me to shame with their goal-scoring skills.

I also noticed the freedom they carried so effortlessly. Unlike the screen-bound solitude of many children, these young ones roamed freely, miles from home and fearless, with no gadgets or hovering concerns. It stirred something in me: a quiet ache for my childhood, when life felt unfiltered, before the digital age had arrived.

I visited several family homes, most of which were a humble constellation of mud huts, each built with a purpose - one for cooking, another for sleeping, and others for storage, all arranged around a central open fire. Their thatched roofs were thick to keep the buildings cool, and the occasional brick house showed the local ambition among the simplicity.

Between trees, homemade washing lines sagged with freshly laundered clothes. Chickens wandered freely, pecking at the floor, and families slept on woven mats laid out on earthen floors.

I sat beside a mother on a wooden stool as we peeled cassava together. Our guide translated her words from the Teso language. She spoke with quiet pride that both her children were in school. Each morning, they fetched water, and each afternoon, they returned to help with chores.

What struck me most was the care taken in the smallest details. Though the home was basic, the men’s shirts and children’s school uniforms were perfectly ironed - crisp, clean, and worn with pride. It was a quiet testament to dignity and discipline.

After the evening chores, the communal fire became a gathering place. Families gathered around it, singing, laughing, and sharing stories. One father told me a local tale about a hare and a drought—a parable with a clear message: greed and secrecy fracture the bonds of the community. It was a wonderful experience to get to know the local people we supported through the projects.

But it wasn’t long before the reality of poverty struck me, and I learned the stories of women who had endured hardship and had fought to survive.

The first time I truly grasped the impact of poverty was while helping in a classroom. The students were focused, diligently repeating the teacher’s English phrases. But one child caught my eye - slumped over her desk, limp and pale, she looked no older than six. At the end of the lesson, I asked if she was alright. The teacher told me she had malaria. I asked if she shouldn’t be at home, resting, but the response was a vague silence that made me feel bad for asking!

As the lesson ended, I moved to the next classroom, but I couldn’t shake the image of that little girl. I stepped outside for air and noticed her wandering across the school field. Then she turned and looked at me. It wasn’t a fleeting glance but a long, piercing stare - it felt like a silent plea for help.

I asked the teacher where she was going. “She’s walking home,” they said. Home was several miles away. There was no transport, no one to accompany her. Just this fragile six-year-old, drained and unwell, making the long journey back to a traditional mud hut where she would sleep on the floor with no access to medical support or medication.

The next moment of deep appreciation came when I met a woman who had launched a small business initiative. She was a widow, a survivor of a brutal attack by two men who had raided her village. In defending herself, she suffered horrific injuries - two of her fingers were severed by a machete. No longer able to work the fields as she once had, she struggled to feed her two children.

She became part of a start-up project, selling Mukene fish - tiny, silver fish from a local lake that she gutted, salted, and sun-dried with care. Alongside these, she sold tomatoes and other vegetables, slowly building a livelihood that allowed her to live independently. She constructed a small clay-brick house from her modest profits, inviting us inside for a cup of herbal tea with quiet pride.

She moved me deeply. In this region, many girls are denied education - families often prioritise sons. At the same time, daughters are expected to work the land and enter arranged marriages at a young age. Many girls do not have a say in who they marry. They are sold for a dowry, and some still have their virginity tested for purity. For widows, the path out of poverty is steep and unforgiving. Their futures are rarely their own.

Her story unexpectedly mirrored an experience of my own, igniting a fire within me to become more involved in women’s empowerment projects. I had my daughter at eighteen, right after graduating from school. I found myself trapped in a violent relationship. Pride kept me silent, and fear kept me isolated. I didn’t want to burden my family with the violence or truth, and I lacked the financial means to leave. So I rode the rollercoaster of his aggression and guilt, absorbing the blows and burying the shame.

One day, while walking through my local town with a black eye and my daughter in her buggy, I felt an overwhelming wave of helplessness. I collapsed and slid down against the wall to the pavement outside the market hall. Something snapped in me, and I found myself sobbing uncontrollably. My daughter was facing away in the buggy, blissfully unaware of the problems behind her. A woman passed by and asked gently, “Are you okay?” I wasn’t. And in that moment, something shifted. It was the start of the decision to take control.

I picked myself up, soothed my daughter, and walked straight to the local police station. I told them everything, the truth I’d buried far too long. That same afternoon, we were taken into refuge with nothing but the clothes on our backs. I didn’t tell anyone where I was, not even my family or friends. I couldn’t risk bringing violence to their doorstep. After a while, I relocated my job to a different town and started over - just me and my little girl.

The stories of these women, of survival, strength, and self-determination, inspired me. They reminded me of my own power and sparked a commitment to helping others reclaim theirs. The most significant gift to give a girl is an education, along with the confidence to be independent.

Having worked as a teacher before my time in Uganda, I was passionately committed to the projects we supported, such as early learning - providing books in Teso and English; training teachers in child-centred learning; offering local role models to communities that demonstrate the benefits of educating girls, and delivering menstrual and sex education to prevent unwanted teenage pregnancies.

We also provided other grassroots initiatives, such as teaching basic math to older girls who had not been in school and had children, and set up Village Loan and Savings Schemes. These schemes are community-based financial groups that offer an accessible alternative to formal banking, especially in rural areas with limited traditional financial services. The women pool their savings and can borrow from the collective fund. The women put forward their needs and borrowed the money at a low interest rate, and the scheme is managed on a trust basis.

I spoke to various women who the scheme had helped, and it had been a lifesaver, especially with paying school fees, uniforms, or setting up micro-businesses. Some women originally used the money to buy maize to sell, but after reaping profits, went on to purchase cattle.

My time in Uganda was always enlightening. We attended lessons, played sports at lunchtime, and participated in the celebrations of the first day at primary school (which included a conga around the school!) We also collected water from the rivers with the children and celebrated the construction of new boreholes that would provide the communities with clean drinking water.

I spent time with locals with different faiths and beliefs. I really enjoyed spending time in a small Muslim community. It broadened my understanding of the local culture and why a man has multiple wives - which is very different to British culture. We celebrated Ramadan with the community, buying the children treats who were allowed to break their fast.

Before we left, the community always put on a show featuring dance and sports, and we ate together a mixed bowl of meat, rice, vegetables, and millet bread. Elders would play the thumb piano, people would sing, and the odd child would join in with homemade instruments.

Working in international development and within the Ugandan communities was one of my most valued and treasured roles. I was passionate about my work, so it felt right to open the kimono and share why I was so invested. I spent time in Mbale, Bukedea, Kumi, and Ngora, visiting many schools and community projects.

As the Brexit vote was cast, funding to these areas dramatically dropped, forcing me to rethink my career plans. However, the experience remains part of me. Now, in a senior role as a director, I can support colleagues in developing their careers, helping others strive for financial independence. Fostering a workplace that values diversity, equity, and inclusion empowers those around me. And stories spread like birds; you never know where they’ll land. So, if you need to empower your life, the first step is to be ready to take control; the next is to seek help. Whether in Africa or England, most of us will have a family member, friend or access to a charity or support group to set us on the right path.

Excellent evocation of struggles and overcoming them. Love the pictures ...and the Mum Dancing! Now I want to go to Uganda.